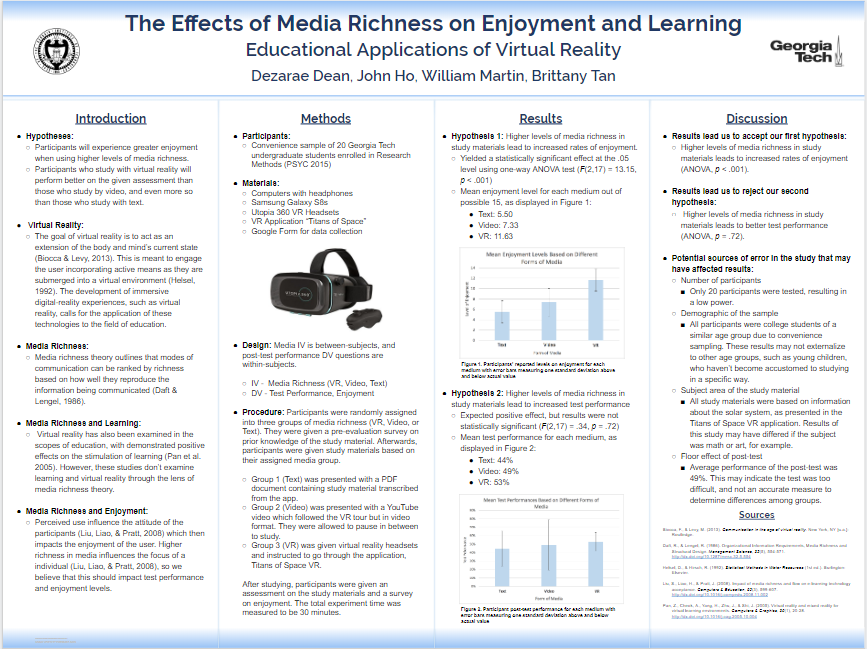

The Effects of Media Richness on Enjoyment and Learning

This undergraduate paper is the combined effort of three undergraduate students (CS, Psych backgrounds) and I that performed a research methods experiment on the effect of different media richness mediums (Text, Video, Virtual Reality). This project was for the course "Psych 2015 - Research Methods", and our poster presentation won 1st place out of all the Spring 2018 submissions voted by judges from the GT Psychology Department. Our poster was honored by being put in the Psychology Department hall of fame, where all previous winning posters are currently on display.

- Client:Georgia Tech Class Project

- Website:Poster Link, Paper Link

- Completed:April 24th, 2018

Background

Over time, humans have evolved the methods of learning in such ways that allow for

accumulating more information and acquiring an overall deeper understanding of learned

concepts. As technology continues to progress, people have begun to develop new techniques of

learning that may span beyond the traditional canon. Soloway, Guzdial, and Hay (1994) explore

the dawn of human computer interaction as engineers of the late twentieth century first began to

implement new designs and interfaces that would make the computer more usable (Soloway,

Guzdial, & Hay, 1994). Azuma (1997) defines augmented reality as a medium with three key

elements: it combines the real and virtual, it is interactive in real time, and it is registered in three

dimensions. This dramatic surge of interest in using virtual reality was seen in the field of

professional education and training (Zahira 2014), which we plan to explore further into

educational retention.

The development of immersive digital-reality experiences, such as virtual reality, calls

for the application of these technologies to the field of education, as they create opportunities for

the improvement of school-based learning. Virtual reality and mixed reality provide a richness of

interaction with information that may outperform more traditional formats commonly associated

education. With previous successful simulations done with VR technology in the aerospace,

graphic design, and medical professional fields (Fowler 2014), and due to the ease of obtaining

such VR equipment for the modern consumer, there is an interest to explore the effect of

educational VR experiences on memory retention. The increased media richness of virtual reality

may lead to higher levels of information retention and aid learning within schools.

Goal

This experiment explores the effect of media richness in educational context, specifically how levels of media richness affect enjoyment of learning and overall effectiveness in learning. Certain studies have shown that there exists relationships between media richness and learning (Liu, Liao, & Pratt, 2008), but no studies encompass the spectrum up to the point of virtual reality. In our study, there was a total of twenty participants who were randomly assigned into one of three different groups. Each group was assigned a different medium—either text, video, or virtual reality—that conveys the same information. All participants were told to study using their assigned medium and then given a post-test where they were assessed on their study material and reported their overall enjoyment of the experience. After conducting one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests on the collected data, the results supported the proposition that media richness has an effect on enjoyment, but did not support the hypothesis that media richness has an effect on learning.

Process

This is an experiment where each group was designated to a condition of media richness to measure the test performance and enjoyment of that media. As a group, we formed two main hypothesis that we wanted to test:

- Participants will experience greater enjoyment when using higher levels of media richness.

- Participants who study with virtual reality will perform better on the given assessment than those who study by video, and even more so than those who study with text.

A convenience sample of twenty Georgia Tech undergraduate students enrolled in Research Methods were used as participants. The participants were given participation credit in the Research Methods class as compensation for their time. Our independent variable was the type of media richness, and it was manipulated into three groups: group one being a text-only condition, group two a video condition, and group three a VR condition. Media richness was measured as a between-subjects variable as participants were only assigned to one of three groups. Our measured dependent variables were enjoyment and test performance. Both dependent variables are within-subjects as every participant had the same post-test. In the post- test, the participants were asked to report their overall enjoyment, their interest in the material, and their perception of how effective it was in learning. These three ratings were summed to calculate their overall enjoyment of the experiment. Enjoyment was measured on an interval scale determining the happiness and excitement for each method of learning. Additionally, the post-test included questions that assessed their learning from the medium they were given. Test performance was measured on a ratio scale determining how accurately a participant answered these questions.

Testing

Results

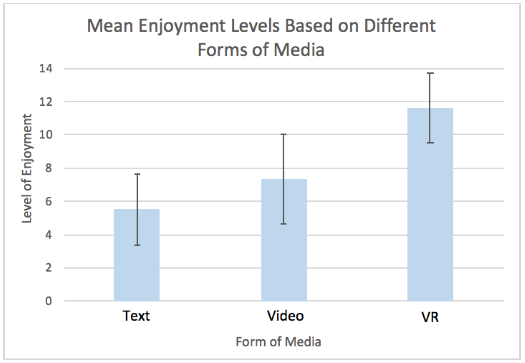

We ran one-way between-subjects ANOVA tests for both hypotheses, where the independent variable for both was the level of media richness. For our first hypothesis, the dependent variable was the participants’ levels of enjoyment. We expected the VR group to have the highest levels of enjoyment, followed by the video group, then followed by the text group. The test results on our experiment data showed to be statistically significant (F(2,17) = 13.15, p less than .001) and supported our hypothesis. The mean enjoyment for each group was 5.50 for text, 7.33 for video, and 11.63 for VR, as shown in the above figure.

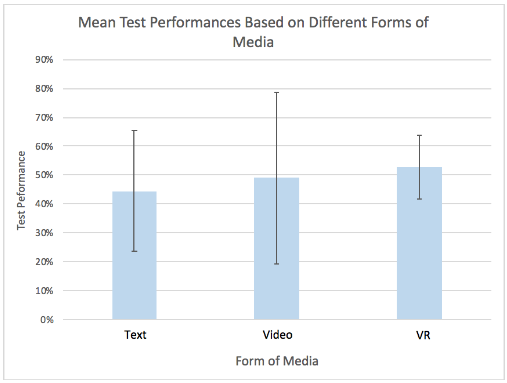

The data for our second hypothesis was also tested using one-way between-subjects ANOVA tests with the same independent variable. The dependent variable for this hypothesis was the participants’ ratio of correct answers on the knowledge assessment post-test. We expected that the VR group would have the highest number of correct answers, followed by the video group, then followed by the text group. The test results on our experiment data showed to be not statistically significant (F(2,17) = .34, p = .72) and did not support our second hypothesis. The mean participant test performance for each group was 44% for text, 49% for video, and 53% for VR, as shown in the second figure above.

Click the paper above to read our complete findings, discussion, and references.

Our results support our first hypothesis, that study materials with higher levels of media

richness will lead to greater levels of enjoyment while studying. When given a survey on their

self-perceived enjoyment of studying, participants who studied with virtual reality reported

significantly higher levels of enjoyment, as compared to video and text.

Our second hypothesis, however, was not supported by our results. Participants who

studied with richer media did not score significantly higher than those who studied with less rich

media, when given an assessment on the material. This is not what we would expect when

considering the effects of media richness theory on learning previously found by Liu, Liao, &

Pratt (2008).

We believe that our lack of significance may be due to a few key errors within our

experiment. Firstly, only twenty participants took place in our study, leading to a very low

power. When examining the average test performance of each group, we do see a general, yet not

significant, rising trend of scores when increasing media richness, and we may find these

differences to become more pronounced and significant simply by increasing the number of

participants.

Additionally, the similar characteristics of participants may have influenced the results,

as they were conveniently selected. All participants were of a similar age, members of the same

psychology class at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and all majoring in either computer

science or psychology at the institute. We believe these similarities may have been too

overbearing to allow our sample to be representative to the general population.

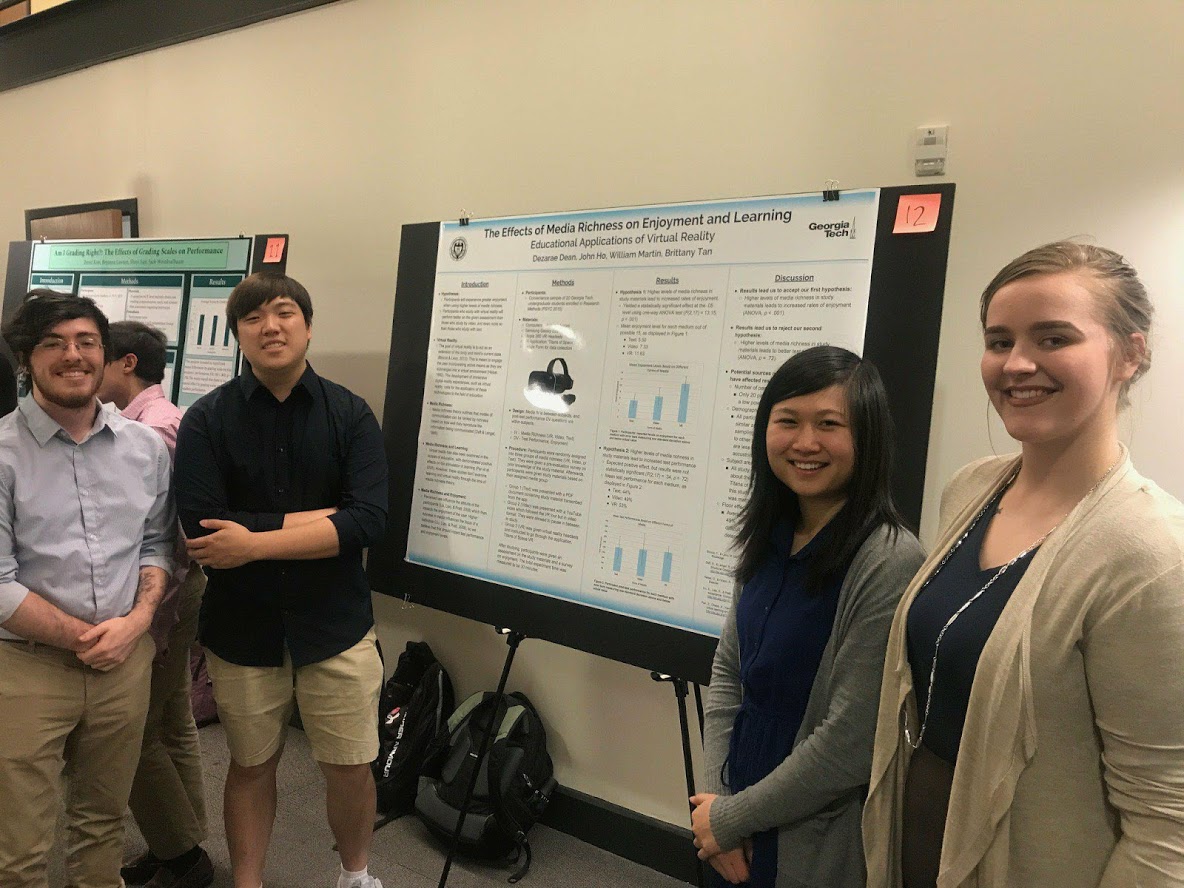

Every group was also required to create a poster and present their findings to esteemed faculty at the Georgia Tech Psychology Department.

This included multiple presentations to more than 10+ faculty members and groups of undergraduate students. Afterwards, judges voted on the

poster they believed to be most interesting and of good quality. Our group was voted *1st Place* and honored by hanging the poster in

the Psychology Department hall of fame, where all previous winning posters were up for show.

You can find the link to view our winning 1st place poster here and both links can also be found at the very top of the page.

Summary

Huge thanks goes to my fellow group members: Brittany, Dezarae, and William for helping me put my VR idea together. Working with undergraduates from a variety of backgrounds really pushed us to produce quality work. As demonstrated by this study, media richness has a significant effect on the enjoyment of learning. Whether or not the learning outcomes are significantly better than studying with traditional media, this alone should be enough to stoke the further creation of educational virtual reality applications. Enjoyment may lead to an increased willingness to study, and thus better academic outcomes within and out of school settings, and this study serves as a recommendation to make enjoyment a consideration when designing learning environments and developing study materials for classrooms of the future.